Shaping Peace: Why Sculpting Is a Powerful Tool for Anxiety Relief

Introduction

1. The Connection Between Creativity and Mental Health

Why Hands-On Art Feels Different

Sculpting as Embodied Mindfulness

2. Emotional Release Through Sculpture

Sculpting Allows Expression of Feelings Too Complex for Words

Externalizing Inner Chaos into Form

Turning Anxiety Into Art

3. Reconnecting with the Body and the Senses

Anxiety and the Disconnection from the Body

Sculpting as a Grounding Practice

“Hands in the material, mind in the present.”

4. The Symbolic Power of Sculpting

Sculpting Inner Strength and Transformation

Totems and Symbols of Resilience

Sculptures as Personal Anchors

5. Shape your emotions

Exercise 1: Sculpt Your Stress

Exercise 2: Shape Your Safe Place

Conclusion

Introduction

In today’s fast-paced, hyperconnected world, anxiety has become an almost universal experience. Between constant notifications, endless to-do lists, and the pressures of modern life, many people are searching for ways to calm their minds and reconnect with themselves. While practices like meditation, yoga, and journaling have gained popularity as tools for managing stress, there’s another, less-discussed path to inner peace: sculpting.

Sculpting is more than shaping or chiseling stone—it’s a deeply meditative practice that invites presence, patience, and expression. As your hands work the material, your mind slows down, grounding you in the moment. Beyond the artistic outcome, the process itself can ease anxious thoughts, release bottled-up emotions, and help restore a sense of balance.

1. The Connection Between Creativity and Mental Health

Engaging in creative activities has a profound impact on the brain and emotional well-being. When we immerse ourselves in art—whether it’s painting, music, or sculpting—the brain releases dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and motivation. At the same time, cortisol, the stress hormone, is reduced, helping us feel calmer and more centered. This chemical shift not only boosts mood but also improves resilience, making creativity a powerful ally in managing anxiety and stress.

You may also like this article : Creating safety within: grounding techniques for an anxious mind

Why Hands-On Art Feels Different

Unlike passive activities such as watching TV or endlessly scrolling on a phone, hands-on art demands active participation. The tactile process of shaping, molding, or carving engages both the mind and body, keeping us present and interrupting cycles of anxious thought. Passive consumption may offer temporary distraction, but it rarely provides the deep sense of engagement and accomplishment that comes from creating something tangible with our own hands. Art taps into a state of “flow,” where time seems to disappear, offering a kind of mental reset.

Sculpting as Embodied Mindfulness

Sculpting, in particular, is uniquely grounding because it requires us to use our hands, focus our attention, and move at a slower, intentional pace. Each press, carve, or adjustment to the material mirrors the principles of mindfulness—anchoring us in the present moment. This embodied awareness not only soothes anxious energy but also transforms it into something meaningful and expressive. Sculpting becomes more than art; it is a meditation in motion, allowing emotions to surface, settle, and reshape into peace.

2. Emotional Release Through Sculpture

Sculpting Allows Expression of Feelings Too Complex for Words

Not every feeling can be put neatly into a sentence. For centuries, artists have turned to sculpture as a way to communicate what words could not. Think of Alberto Giacometti’s elongated figures, which seem to embody loneliness and fragility, or Louise Bourgeois’s towering spider sculptures that symbolized both protection and fear. (photo here)

These works show how form can express emotional depth far beyond language. Modern research in art therapy echoes this, noting that tactile creation provides an outlet for emotions that otherwise remain locked inside. Just as journaling translates thoughts into words, sculpting translates feelings into touchable shapes, bridging the gap between the inner self and the outside world.

Externalizing Inner Chaos into Form

When anxiety builds up, it often feels abstract and overwhelming—like a storm without a center. Sculpting gives that storm shape. For example, an art practitionner might encourage a participant to press their anxiety into clay, shaping it into something rough and jagged, then smoothing it over as a symbolic act of calming the mind.

This process mirrors what artists like Eva Hesse explored in their work—turning personal pain into tangible, abstract forms (photo here). Books like The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk also highlight how trauma and anxiety live in the body; by working with materials, people can externalize that weight and begin to process it. Sculpting doesn’t just distract—it transforms vague chaos into something you can see, touch, and eventually let go of.

Turning Anxiety Into Art

The beauty of sculpting is that even the simplest creations carry meaning. A lump of papier-mâché shaped into a nest could represent the longing for safety, while a cardboard figure with exaggerated features might capture the feeling of being watched or judged. In one popular TED Talk on art and healing, artist Candy Chang described how creative acts give people a way to share unspoken fears, turning private struggles into communal understanding. Similarly, many art programs in hospitals and mental health clinics use sculpture work to help patients express their inner states. In this sense, sculpting transforms anxiety into art—not by erasing it, but by reframing it as something expressive, creative, and ultimately, healing.

3.Reconnecting with the Body and the Senses

Anxiety and the Disconnection from the Body

Anxiety often pulls us into our heads, leaving us caught in loops of racing thoughts, “what ifs,” and worst-case scenarios. Neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux, in his book Anxious: Using the Brain to Understand and Treat Fear and Anxiety, explains how the brain’s fear circuits can dominate our awareness, cutting us off from signals coming from the body. This disconnection is why anxious people may feel restless, numb, or even unaware of their physical state. Essentially, anxiety hijacks the mind and detaches us from the grounding presence of the body.

Sculpting as a Grounding Practice

Sculpting reverses this disconnection by re-engaging the senses. The texture, the resistance of papier-mâché, or the movement of carving directs attention back into the body. Research in art therapy, such as Cathy Malchiodi’s The Art Therapy Sourcebook, emphasizes that tactile creative practices reduce stress by stimulating the sensory and motor systems. Studies also show that hands-on, rhythmic activities lower cortisol levels, helping regulate the nervous system. Unlike abstract thought, sculpting requires embodied participation—pressing, shaping, and moving—each action gently pulling awareness out of the anxious spiral and back into the present.

Hands in the Material, Mind in the Present

The phrase “hands in the material, mind in the present” captures the essence of sculpting as embodied mindfulness. Psychologist Bessel van der Kolk, in The Body Keeps the Score, notes that trauma and anxiety are stored not just in thoughts but in the body, and physical practices help release this tension. By anchoring awareness through texture, touch, and rhythm, sculpting works like a sensory meditation. The repetitive motions and tangible feedback invite a flow state similar to mindfulness meditation, where body and mind move together. In this way, sculpting becomes both a grounding ritual and a therapeutic bridge between the physical and emotional self.

4. The Symbolic Power of Sculpting

Sculpting Inner Strength and Transformation

When we create forms with our hands, we often shape more than just material—we give physical expression to inner qualities like strength, balance, or transformation. A solid, upright figure might represent resilience, while a spiral form could symbolize growth and renewal. Carl Jung, who often used art with his patients, described such symbolic creations as pathways to the unconscious, helping people embody parts of themselves they couldn’t easily put into words. Through sculpting, the intangible—courage, healing, or change—becomes tangible, something we can hold, see, and revisit.

Totems and Symbols of Resilience

Throughout history, people have made totems, statues, and symbolic objects to remind themselves of their capacity to endure. Indigenous cultures carved figures to embody protection or guidance, while modern artists like Henry Moore used abstract shapes to evoke stability and harmony. In personal practice, sculpting a small totem, figure, or even an abstract form can become a symbolic act of reclaiming strength. These shapes serve as daily reminders that resilience is not only a concept—it can be represented, celebrated, and reinforced through art.

You like it ? I have a program for you, click here

Sculptures as Personal Anchors

In moments of stress or anxiety, sculpted objects can serve as personal anchors. Just as a worry stone can be carried in a pocket and rubbed for comfort, a handmade sculpture can hold emotional weight, grounding us when life feels unstable. Cathy Malchiodi, a leading voice in expressive arts therapy, notes that objects made in therapeutic art sessions often become meaningful keepsakes, helping people reconnect with feelings of safety and empowerment. A sculpture doesn’t have to be large or polished to carry power—it simply has to embody personal meaning, acting as a touchstone for calm, strength, and balance when it’s most needed.

Read this article : How to Prevent Burnout: 5 Creative Rituals to Reclaim Your Energy

5. Shape your emotions

Sculpting can become a mindful ritual for exploring and soothing emotions. Start with a simple salt dough or use store-bought play dough, and create a calming space with soft music, candles, or silence.

Salt dough recipe :

2 cups of flour

1 cup of table salt

1 cup of water

(You can keep it in the fridge few days)

Instead of aiming for a finished “artwork,” allow the process itself to guide you—pressing, rolling, or smoothing as your feelings shift. Daily 10–15 minute sessions are enough to build a habit of emotional release and grounding. Over time, these small, tactile practices can help you reconnect with your body, express feelings too complex for words, and find balance through the rhythm of your hands.

Exercise 1: Sculpt Your Stress

Take a piece of salt dough or play dough and imagine it as a container for your stress or anxiety.

With your hands, press, squeeze, or twist the dough in whatever way feels natural, letting your movements reflect your emotions.

You might end up with jagged shapes or compressed lumps—that’s okay. The goal isn’t to create something beautiful but to transfer the tension from your body into the material.

When finished, you can choose to smooth it out as a symbolic act of calming, or even reshape it into something lighter and softer.

Let it dry 1 day and paint it

Exercise 2: Shape Your Safe Place

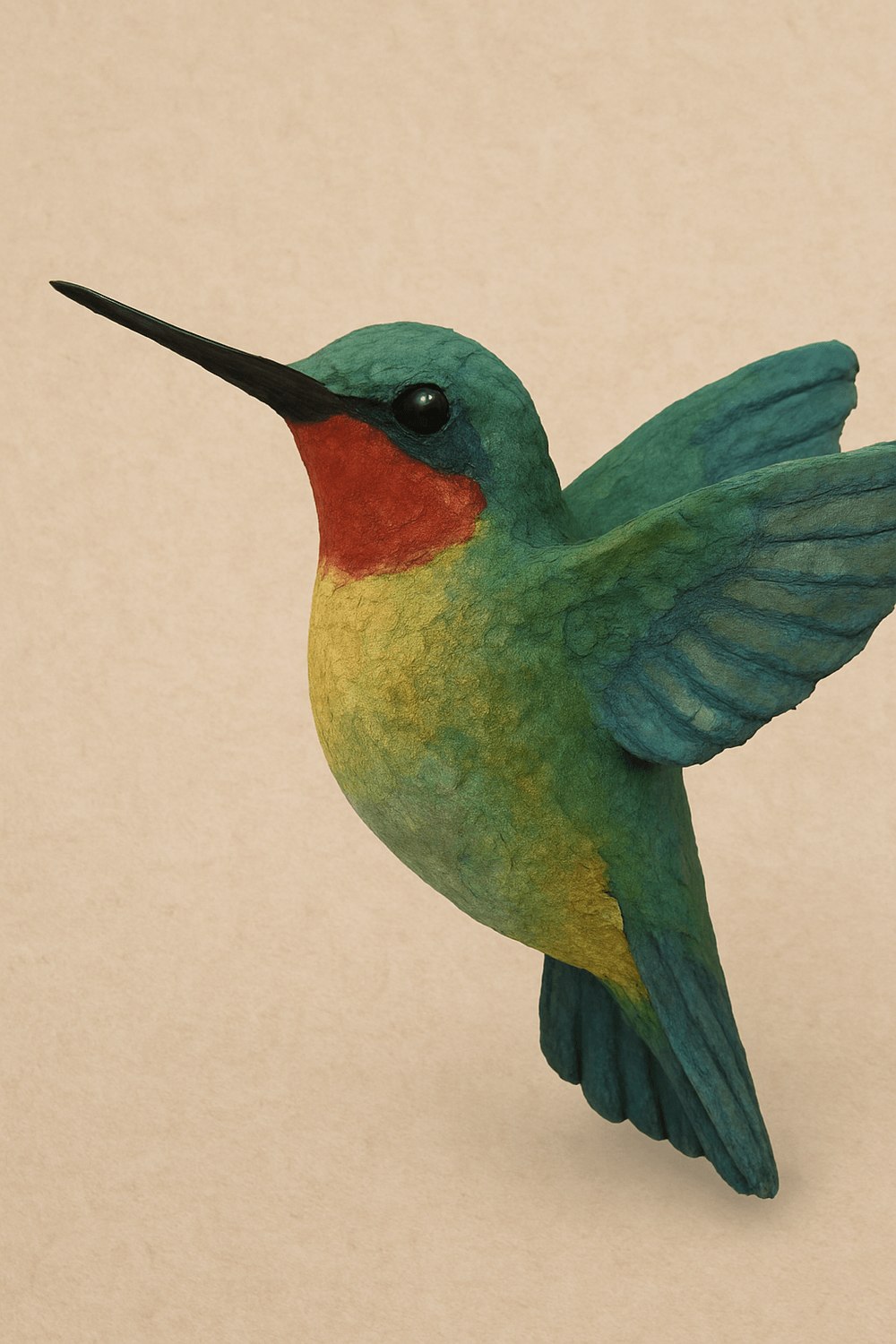

Using the same material, sculpt a symbol of safety or calm. This could be a small house, a protective animal, or even an abstract spiral or sphere that represents balance.

Focus on textures—smooth edges, gentle curves, or repetitive patterns that bring comfort as you work. This piece can become a physical reminder of your inner resilience and a touchstone you return to when you need grounding.

Let it dry 1 day and paint it

Conclusion

Sculpting is more than a creative pastime—it’s a healing journey that reconnects us with our bodies, grounds us in the present, and gives form to emotions that words can’t capture. Through touch, rhythm, and mindful creation, it transforms anxiety into something tangible, expressive, and deeply calming. The act of shaping clay, dough, papier mache or any material is not about producing a masterpiece, but about honoring the process of release and renewal.

So the next time anxiety begins to rise, step away from the noise of your thoughts, put your hands in the material, and let peace take shape. In each press, curve, and texture lies an invitation to slow down, breathe, and discover the quiet strength within yourself.

✨ Bonus Invitation

Looking for support in bringing these practices into your daily life? Join my newsletter and get free access to a monthly online workshop.“3 exercises to letting go”